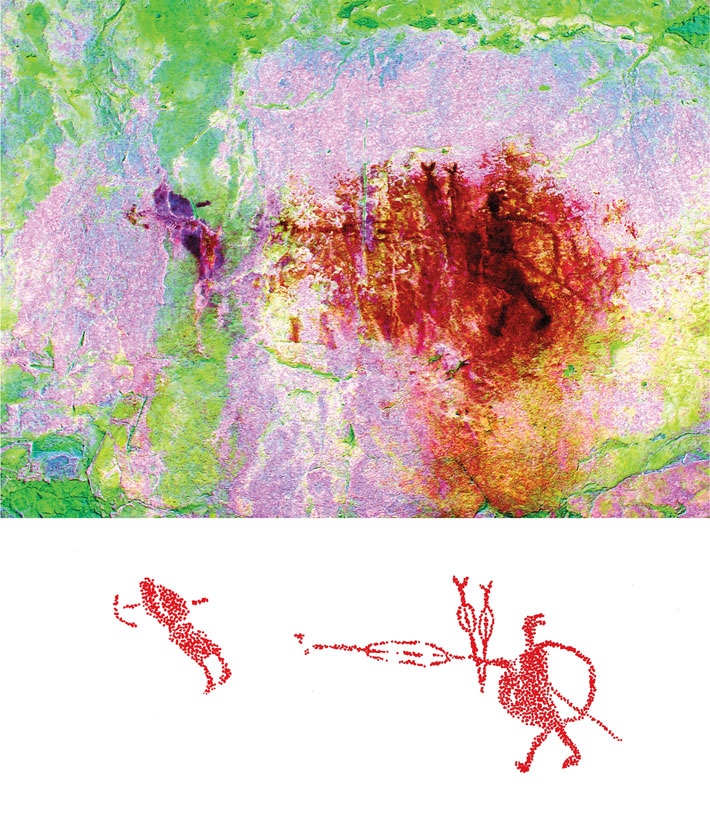

In the Lower Pecos Canyonlands of southwest Texas, a mile upstream from where the Pecos River flows into the Rio Grande, the White Shaman rock shelter is carved into a cliff face at the end of a limestone canyon. Here, in a small alcove, a 26-foot-long collection of pictographs stretches across a smooth wall that faces west. The pigments have faded over time, but a dense profusion of surreal figures, some highly abstract, others seemingly human or animal-like, are still visible. The setting sun can intensify the figures’ yellow and red colors, while a full moon illuminates white images, including the elongated headless human figure that gives the site its name. Similar rock art figures, some up to 20 feet high, decorate more than 200 rock shelters within a 90-mile radius around the confluence of the Pecos and the Rio Grande. Hunter-gatherers who lived here from about 2500 B.C. to A.D. 500 created these paintings, which belong to a tradition known today as the Pecos River Style.

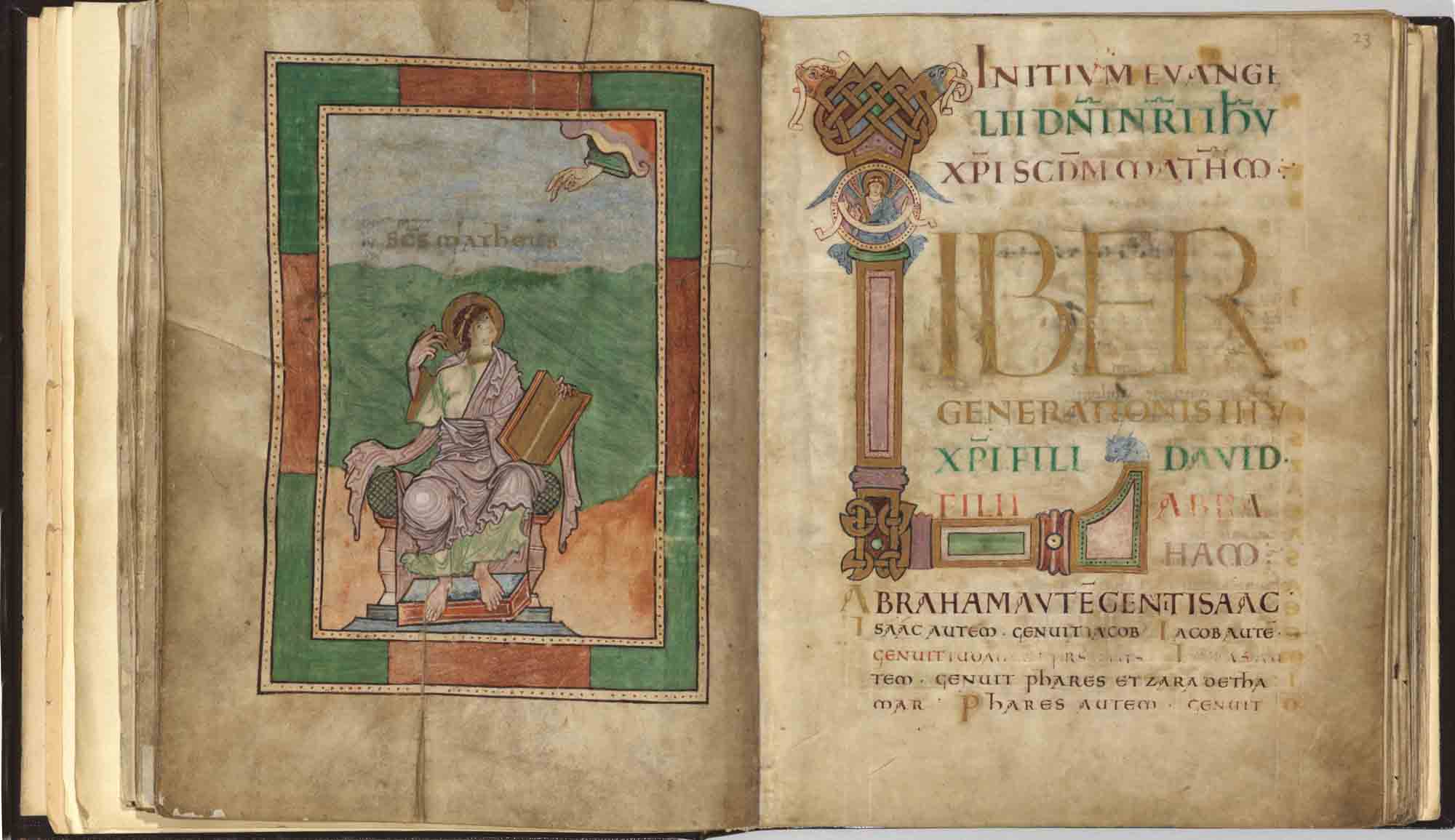

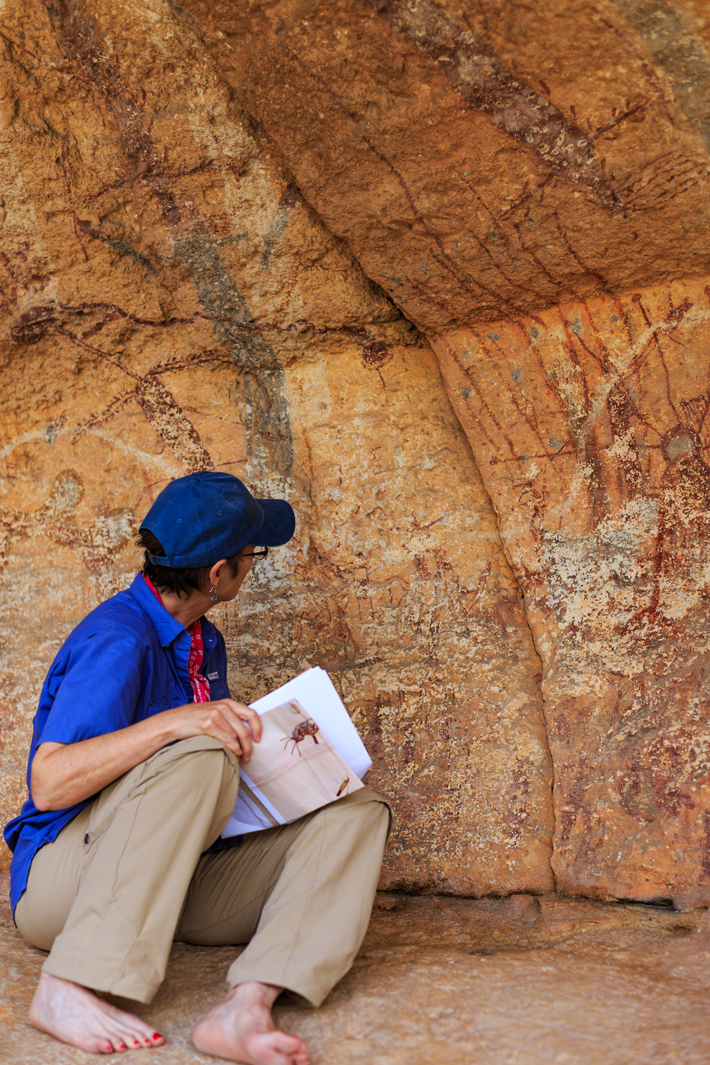

These fantastical pictographs have long defied easy interpretation, and many archaeologists have resisted speculating about their meaning at all. Some believe the often bizarre images were made by shamans to recreate hallucinogenic visions they experienced while under the influence of stimulants. In recent years, Texas State University archaeologist Carolyn Boyd, a former professional artist, has proposed that they represent something much more complex. She has put forth the theory that the pictographs at White Shaman, and perhaps other Pecos River Style paintings, record the beliefs of ancient peoples whose descendants still live in Mexico today. What’s more, Boyd is convinced that by using scientific and ethnographic methods, we can begin to understand these narratives. “These are painted texts,” says Boyd. “I think we can read them, just as the people who created them must have read them.”

Boyd first visited White Shaman in 1989. At the time, she was making a living as a muralist, executing large paintings on commission. When she saw the figures there, she felt a shock of recognition. “I instantly knew that it was a mural,” she recalls. Some scholars believe the painting was created over an extended period of time, with multiple people painting unrelated figures. But Boyd felt that couldn’t be right. “I could tell at once that it had been planned and conceived as a single composition,” says Boyd. “And because I was a muralist, I knew the skill it took to produce something like this, and to do it so beautifully. I was awed.”

For one thing, it was clear to her that some kind of scaffolding had to have been erected in order to complete some of the pictographs, which can stretch as high as 13 feet. As she made her own renderings of the painting’s images, she began to think the work could depict a battle scene of some sort. She suspected that a prominent row of five identical faceless humans with black bodies, topped with red and carrying what appear to be staffs, could represent warriors. But she also knew she was viewing the painting through an artist’s eyes. To talk about her ideas with researchers, she was going to need hard evidence. “I was convinced it was a composition, but I also knew that the archaeologists were going to say ‘Show me the data,’” says Boyd. The experience inspired her to return to school and pursue a doctorate in archaeology.

Boyd has spent the last three decades studying White Shaman and other Pecos River Style pictograph sites, but archaeologists have been recording and debating these sites since the early twentieth century. “It’s such an unusual tradition, really unlike almost any other rock art on Earth,” says Witte Museum curator of archaeology Harry Shafer, who has worked in the Lower Pecos since the 1970s. “It’s also unusual to have such a dense cluster of these sites, and there are probably more we haven’t discovered.” The first scholars to interpret the paintings thought they were linked to a hunting cult that ritually consumed mescal beans. Many contemporary Native American groups, such as the Apache, practice rituals involving the beans, and it was thought that the Pecos River Style paintings had been created during similar ceremonies. The idea that they were made by shamans was refined in the 1980s by University of Texas archaeologist Solveig Turpin, who posited that shamans may have produced the paintings during periods of conflict in order to reinforce their claims to leadership. During her long career, Turpin also identified at least 35 more Pecos River Style sites across the Rio Grande in the Mexican state of Coahuila, which is relatively unexplored by archaeologists.

Boyd, for her part, set out to document White Shaman in detail. She also painstakingly recorded four other well-known rock shelters decorated with Pecos River Style rock art, including Rattlesnake Canyon, where pictographs are spread out on a 100-foot-long panel. She hoped to explore the possible meaning behind not just the White Shaman site, but the entire school of Pecos River rock art, and to do it in a way other archaeologists could test. “The good thing about rock art is that, unlike a dirt site, when you study it, you don’t destroy it,” says Boyd. “And other researchers can come back to the site to verify your work.”

In carefully documenting White Shaman, Boyd realized that her initial impression that the painting represented a battle was probably wrong. There were simply too many motifs and figures in the mural for it to make sense as a depiction of a real-world battle. But she knew that the mural’s images were not random, and that at some level it was telling a story. She notes that planning Pecos River Style murals probably took months. The artists would have needed time to gather the minerals, the plants, and the animal fats they used to make their pigments, and a ritual would likely have accompanied each step. Then there was scaffolding to be built. “The effort was immense,” says Boyd. There was no way, she believed, that the scenes depicted could be unrelated to each other.

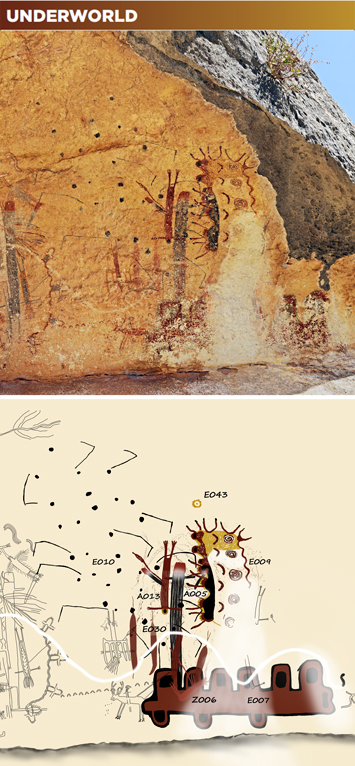

She soon noticed that Pecos River Style rock art panels often seemed to be separated into three tiers, sometimes divided by wavy lines. She knew from reading ethnographic accounts that ancient Mesoamerican people conceived of the world as divided into three realms: the underworld, our world, and the world above. Many cultures believed that these worlds could be divided, one from another, by a snake, not unlike the wavy lines she was seeing at Pecos River sites. “The similarities with the Mesoamerican ideas struck me,” says Boyd. “I thought it made a lot of sense to see if there were connections between Pecos River Style motifs and those in the ethnographies.” Boyd found that a curious motif she identified in the White Shaman mural, black-tipped deer antlers, also occurred in the art of the Huichol, a people who live in isolation in the mountains of western Mexico, and whose traditions are thought to have changed little since the arrival of the Spanish, with whom they had minimal contact. The Huichol speak a Uto-Aztecan language, part of a language family also spoken by the Hopi and Utes of the American Southwest and the Nahua, or Aztec, peoples in central Mexico. As she studied Huichol culture, Boyd learned that every year, its shamans make a 600-mile pilgrimage to what they regard as their sacred homeland to gather peyote, continuing an ancient practice. Carrying bows and arrows, the pilgrims are metaphorically guided to their destination by deer, which are closely linked to peyote—the Huichol consider peyote and deer a single sacred symbol. They believe that as the sacred deer moves, it creates the peyote in its hoofprints. At the end of their journey, each pilgrim shoots an arrow at a peyote cactus before gathering the disk-shaped buttons, which have hallucinogenic properties. “By shooting the arrow,” says Boyd, “the pilgrims metaphorically sacrifice both the peyote and a deer.”

At White Shaman, Boyd found that impaled deer with black-tipped antlers were depicted near fringed black dots that were also impaled with spears. These fringed dots, she reasoned, could depict peyote sacrificed during a ritual roughly similar to the one practiced by Huichol pilgrims today. The five black figures who she initially thought were warriors could be depictions of peyote pilgrims. In the 1930s, archaeologists digging in a rock shelter known as Shumla Cave 5 near the White Shaman site found peyote mixed with other plants to form disks that represented peyote buttons. Those artifacts date to 5,700 years ago, so peyote rituals must have had a deep history in the region.

Boyd concluded that the entire painting is a visual set of instructions that communicated how to carry out a peyote ritual. “I knew the mural wasn’t just the product of a person in an altered state,” she says. “I thought it was a well-ordered document recording an ancient ritual, one that has endured in some form until today.”

In 1998, Boyd founded Shumla, a research and education center devoted to the archaeology of the Lower Pecos, in Comstock, a small town a few miles from White Shaman. (The organization’s name is officially an acronym for Studying Human Use of Materials, Land, and Art, but is also a reference to the Shumla Caves archaeological sites, which in turn take their name from a nearby ghost town.) With her colleagues, Boyd has developed a method to record Pecos River Style rock art, creating highly accurate digital renderings by relying on many different technologies, including laser mapping and high-resolution panoramic photography. They also use portable X-ray fluorescence to analyze pigments’ elemental composition. “These technologies allow us to test what we see with the naked eye,” says Boyd. “And often we’ve found that what we thought about a painting is simply wrong.” As she helped develop Shumla’s technological expertise and its educational programs, Boyd continued to examine White Shaman, and came to think that the mural was even more meaningful than she had initially suspected. In 2008, the Shumla team began recording the site with their battery of new techniques, and they found a number of previously unseen repetitive designs and patterns. “We got the sense that the mural might be telling a deeper story,” says Boyd, “something that went far beyond a depiction of a peyote ritual.”

In 2010, while creating a digital rendering of a red human figure with antlers topped with the black peyote symbol, Boyd had an epiphany. “I realized that the black dots had been painted first, which didn’t make sense initially. Why paint black dots first and then a red figure connecting them?” Using digital microscopy, the team found that there was a strict stratigraphy to Pecos River Style paintings. In some 98 percent of the pictographs, the different colors were always applied in the same order, with black imagery being laid down first, then red, yellow, and finally, white. “The pictographs have such a deliberate structure,” says Boyd. “That tells us without a doubt that they were carefully planned compositions, single murals that conveyed meaning together.”

Boyd returned to accounts of Huichol mythology, and soon began making new connections with that culture’s different creation stories, as well as with the myths of other groups, especially the ancient Nahua. She found so many similarities in motifs and sacred symbols that she came to believe the rock art at White Shaman depicts a core of archaic beliefs that still survive today. “These people weren’t necessarily the ancestors of the Huichol or Nahua,” says Boyd, “but I think they shared certain elements of the same ancient Uto-Aztecan belief system.”

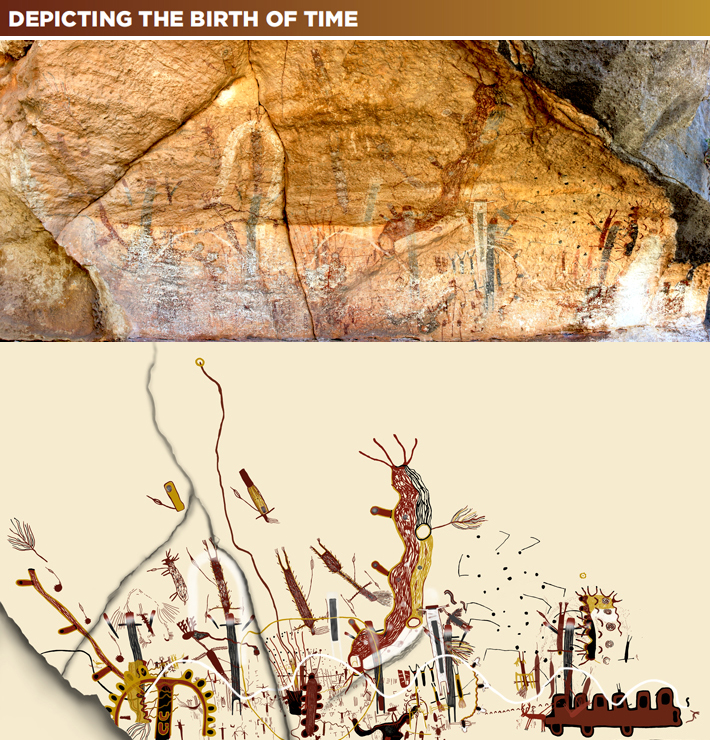

According to Boyd’s careful analysis of each motif at the site, the mural tells several different narratives simultaneously. Read from left to right, the mural seems to tell the story of the birth of the sun and the dawn of time. One of the first motifs she identified as part of this story was a large crenellated arch on the mural’s left side. “This is Dawn Mountain,” says Boyd, “the primordial arch through which the Huichol and Nahua believe the sun first came into the world.” Rising above the arch is the human figure with antlers whose colors she first identified as having a specific stratigraphy. She equates this figure with the sacred deer that was sacrificed to enable the sun’s rise in Huichol mythology. The five figures marching across the panel are not just peyote pilgrims, but the five primordial ancestors of Nahua and Huichol myth who were led to Dawn Mountain by the sacred deer. Boyd argues that, rather than staffs, what the figures are holding are torches to help fuel the first sunrise, after which the ancestors were transformed into gods. Fundamentally, she believes the mural depicts an ancient creation myth.

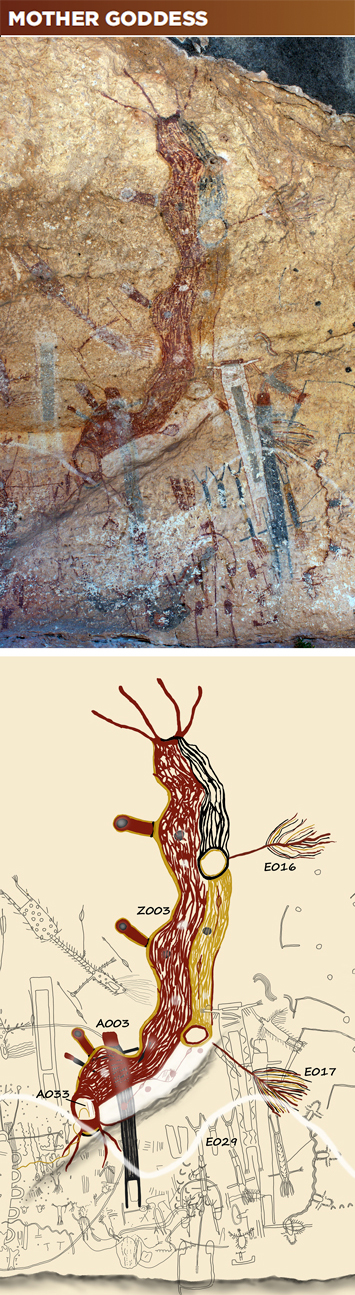

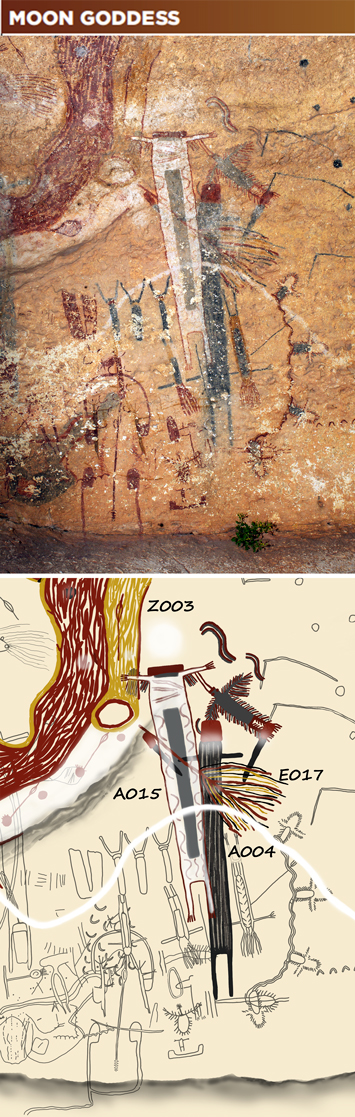

Each of these ancestors is painted next to a unique and elaborate figure. “I think these depict the god that the ancestor became,” says Boyd. The central primordial ancestor is painted next to a six-foot-tall half-serpent, half-catfish figure, which could depict the Earth Goddess or mother of all deities. For the Huichol, this goddess is a conflation of a snake and a catfish. It is positioned at the center of the mural, and could be preparing to meet the sun at midday, as the goddess does in Huichol tradition. Close by is an ancestral figure painted next to the headless white figure that gives White Shaman its name. Boyd believes this image depicts the decapitated Moon Goddess, who is associated with the west and the winter solstice in Nahua myth. Another curious figure at the feet of the possible Moon Goddess struck Boyd as significant. “You can clearly see a red depiction of a man in a boat,” says Boyd. “In Huichol myth, the Moon Goddess saves a single man from the Great Flood in a canoe.” The Huichol today still recreate this mythic watery escape in yarn.

On the far right of the mural, the last primordial figure is depicted next to an upside-down humanoid Boyd believes is a solar figure. The two are painted next to a band of black and red with nine bulges. The colors red and black and the number nine are both associated with the underworld in Uto-Aztecan myths, and this could represent the underworld in the west, where the sun sets and humans were believed to have first come into the world. A nearby caterpillar-like figure reinforces this interpretation, since both the Nahua and Huichol linked caterpillars with the underworld and the night. The underworld was also associated with water for the ancient Nahua, and Boyd notes that this section of the mural is on a natural water seep that has leached the paintings of their vibrancy, but whose association with the underworld motif was probably a deliberate strategy. “To me, it’s clear that that they recognized this location where water is seeping as the natural place to picture the underworld,” says Boyd. A deer is depicted standing next to this feature, and could be another representation of the sacred deer that led the ancestors to Dawn Mountain and was sacrificed to allow the sun to enter the world. A wavy white line that connects all the ancestral beings could represent the path of the sun and the Mesoamerican concept of the Flower Road, a celestial pathway along which the sun, gods, and the ancestral beings are all thought to travel.

Where other scholars saw a collection of unrelated images, Boyd sees a deliberately crafted master narrative. She thinks that even the sequence the colors were painted in enhances this story. Black was the color of femininity and primordial time, and it was applied first. Then came red, a color associated with masculinity, blood, and the color of the sky just before sunrise. The next color was yellow, associated with the rising sun. Finally, white, the light of midday, which renders the world shadowless, was applied.

“It’s a narrative about the creation of time,” Boyd says, “but the imagery also depicts the sun’s daily cycle and records the changing seasons.” She notes that it could even be seen as a metaphor for the transformations each person experiences through the course of life. She believes that the White Shaman mural helped the archaic people who made it understand the world around them on many levels.

A number of archaeologists have embraced Boyd’s bold interpretations. “What she’s done is impressive,” says Shafer. “There’s no question it is rigorous and grounded in good ethnography and good archaeology.” Texas Tech art historian Carolyn Tate, who is an authority on Olmec art, also thinks the connections Boyd has identified between the Pecos River Style and Mesoamerican traditions are provocative, even if not yet conclusive. She says, “Some of the motifs she’s identified—such as the crenellated arch—these are visual patterns you see in Nahua manuscripts.” Tate thinks it will take further research to solidify the connections between the Pecos River sites and Mesoamerican beliefs, but credits Boyd with making her and her colleagues aware of a tradition that wasn’t on their radar. “This style is the oldest large group of pictographs in the New World and it’s been overlooked by Mesoamericanists. She’s making us pay attention to the idea that this could be the northern frontier of Mesoamerica.” Tate also notes that Boyd’s methods of recording the murals will have a major impact on the field: “Just the technology itself will lead to a new era of rock art studies.”

Some researchers have raised doubts about Boyd’s interpretations, pointing out that she is linking myths and motifs that could be separated by thousands of years. Others question the assertion that each of these motifs could have astronomical significance. Boyd says, “There’s this idea that hunter-gatherers wouldn’t have been so concerned with celestial events and tracking the seasons, but that’s just not true.” She remarks that even though they had no crops to harvest, hunter-gatherers’ lives were also deeply impacted by the changing seasons, which they would have had to carefully observe. “They would have been just as concerned as agricultural peoples. Time is written into the White Shaman mural.”

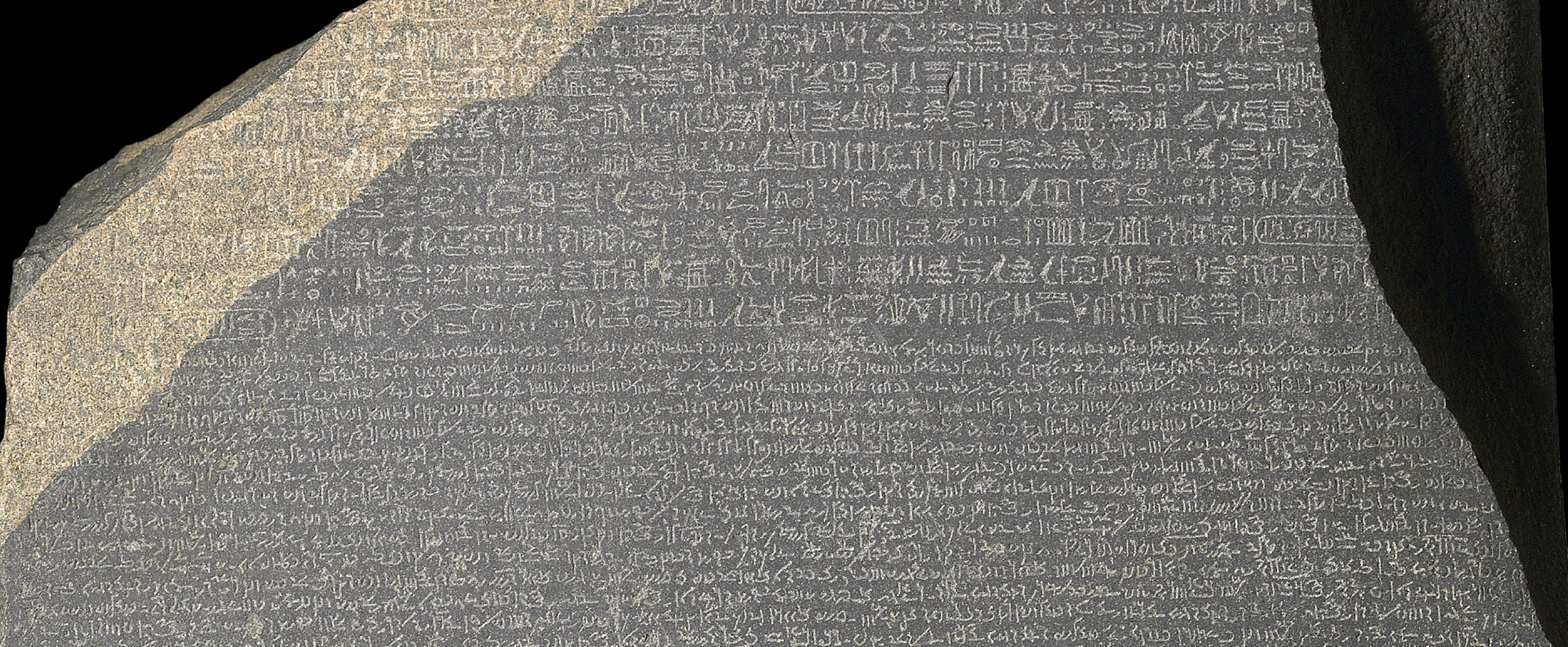

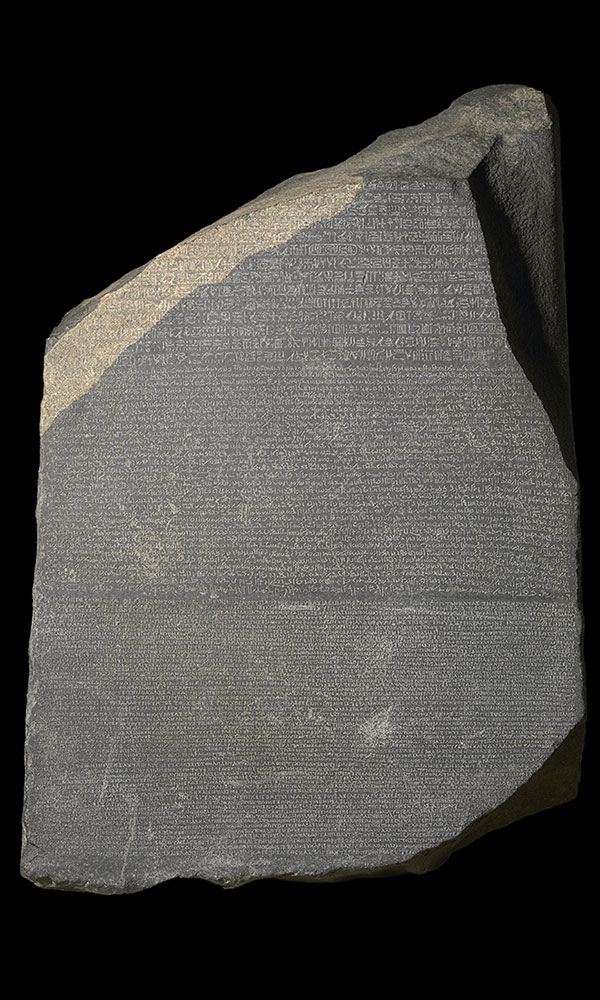

This year, Shumla began the Alexandria Project, an effort to record every single rock art site in the region in as much detail as White Shaman. Its name reflects Boyd’s deep belief that these murals are texts, analogous to the books once housed in the Library of Alexandria. Like the volumes in that ill-fated library, many of the sites are threatened, whether by fluctuating water levels or vandalism. “It is urgent that we make as complete a record as we can, now,” says Boyd. As a case in point, Shumla just completed an exhaustive survey of Rattlesnake Canyon, the future of which is bleak due its location on a reservoir whose rising waters are threatening to erode away the site’s pictographs.

Research director and archaeochemist Karen Steelman is overseeing the effort, and she has set up a new Shumla lab that will allow the team to use a process known as plasma oxidation to extract organic carbon from minute paint samples, which can then be radiocarbon dated. Steelman is developing a comprehensive plan to radiocarbon date as many of the pictographs as possible. “Ideally, this project will give us the chance to date a large number of Pecos River rock art sites,” says Steelman, who notes that previous radiocarbon dating has largely been limited to endangered pictographs, which could be skewing how archaeologists understand the development of the tradition. “This should allow us to see patterns,” says Steelman, “and help us understand how the art changed and evolved through time.”

While Boyd is no longer actively overseeing Shumla’s fieldwork, she is still heavily involved in its efforts, and cannot stop thinking about White Shaman. “I am continuing to learn more and more about this mural,” she says. “Every time I come back to it I see something new.” She also says that it is high time for her to shift her focus to other sites, such as Rattlesnake Canyon, in hopes that she can unlock their narratives and add to the stories told by White Shaman.